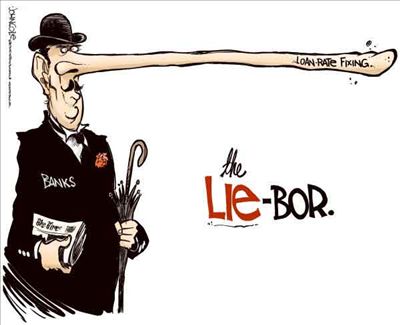

Just when you thought you had seen the last of “bankers gone wild,” up jumps the LIBOR scandal. LIBOR—the London Interbank Offer Rate—is the mechanism that sets interest rates for everything from credit cards and home mortgages to all sorts of exotic derivative investments. It involves 18 global banks, including JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Citigroup in the U.S.

Just when you thought you had seen the last of “bankers gone wild,” up jumps the LIBOR scandal. LIBOR—the London Interbank Offer Rate—is the mechanism that sets interest rates for everything from credit cards and home mortgages to all sorts of exotic derivative investments. It involves 18 global banks, including JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Citigroup in the U.S.

Fiddling with the LIBOR in one direction or another triggers a cascade of events, most of which cost Mr. and Mrs. America dearly. As one of the traders who was brought into the process by another conspirator wrote ironically to his colleague: “Dude, I owe you, big time!”

Indeed. Teachers, firefighters, police officers and many other public workers—from drivers, janitors, accountants, clerks and zookeepers—lost wages, pension income and jobs, big time, as a result of this secret manipulation in the back office of banks in Europe and the U.S. The losses resulting from this conspiracy are expected reach into the trillions of dollars, according to experts.

Among the tangled tentacles of this scheme is what happened to “interest rate swaps” one of those suspicious and largely unregulated “derivative” investments that make speculators wealthy and schmucks out of the rest of us.

While the bankers were fiddling with LIBOR, accountants and bookkeepers in scores of taxpayer funded institutions (governments, hospitals, school boards and the like) were confronted with shrinking tax rolls and increasing borrowing costs as they pored over their books to try to figure out how to pay the bills. Along came the brokers and salesmen from the financial industry with portfolios of investment options, including swaps. Simply put, the brokers offered—and many public officials okayed—a bet, or hedge, that they could swap the interest rates that they were paying for a floating rate that was initially lower, but liable to rise or fall before the debt was paid. And, rise they did because, apparently, the game was rigged.

Today, the headlines are filled with dire stories of cities and counties, large and small, dealing with bankruptcy. For politicians, the preferred solution is to hack away at jobs and services and opt for “austerity.” Behind the scenes though, the speculators who sold shaky derivative investments stand first in line for whatever funds are in the kitty. That’s how bankruptcy works. The lawyers and bankers get their money first. Everyone else has to accept pennies on the dollar, or worse, nothing at all.

The revelations about LIBOR have prompted some government entities to seek redress in court. The city of Baltimore, for example, is going to court to try and claw back what it now sees as a loss from fraud.

Baltimore City Solicitor George Nilson said that the rate manipulation meant that the city lost out on money when it needed it the most.

“The injury we suffered during the time we suffered it hurt more because we were challenged budgetarily,” Nilson said. “Every dollar we lost due to illegal conduct was a dollar we couldn’t pay to keep open recreation centers or to pay police officers.”

Other institutions—especially the big public employee pension funds—are currently reviewing their books to see how LIBOR manipulation might have affected their bottom lines.

Robert Diamond, CEO of Barclays of London, one of the key players in this price fixing scheme, has admitted that he fibbed in reporting interest rates to the panel. Diamond claims he only did it to “protect” Barclays, but it turns out other traders did the same thing to expand their profits.

Hrumph! Exclaimed banking authorities in the U.K. They proceeded to rap Barclays on the knuckles with a $450 million dollar fine, which the bank’s shareholders promptly paid, while Barclays promised to sin no more.

Now, if an ordinary citizen fibs to bankers to, say, qualify for a car loan, the law calls that bank fraud and prescribes serious penalties, including possible jail time. When the shoe is on the other foot, typically, authorities extract a promise from the offending banker that they won’t repeat the behavior in return for the government’s promise not to prosecute, ostensibly, because it’s so expensive.

According to news accounts, LIBOR rates were set on a bogus basis for over four years—from 2005 through 2009.

As Lee Saunders, newly-elected president of the 1.6 million member American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) noted recently, “reckless behavior” by banks like J.P. Morgan Chase and other Wall Street firms has cost the jobs of more than 600,000 state and local government workers and prompted 43 states to reduce pension programs. “Nothing less than the very fabric of our country’s retirement security is at stake,” Saunders said. LIBOR, he added, is just the latest in a long string of similar scandals and “evidence that Wall Street greed and recklessness know no limits.” And, he warned, taxpayers are “still on the hook for future bailouts.”

The banking and finance industry bought its way out of regulation in the late 1990s when Congress acted to repeal most of the restrictions that had been enacted after the Great Depression in the 1930s.

Over the past decade, the industry has spent over $2.8 billion in lobbying funds and another $1 billion in political contributions to stay deregulated and weaken any efforts to erect new safeguards for the public. It continues to resist the toughest elements of the

Dodd-Frank law passed in the wake of the banking bailout four years ago.

From the point of view of the 10 biggest U.S. banks, lobbying and influence money has been well spent.

U.S. banks earned a record $35.3 billion in profits in the first quarter of 2012, a jump of nearly 20 percent over the same quarter in 2011. Sixty-seven percent of U.S. banks reported improved earnings in the quarter, buoyed by profits from loans and customer fees. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) reported that the biggest banks (among them are the usual suspects—Bank of America, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase and Wells Fargo) accounted for more than 80 percent of first quarter profits even though they represent a mere 1.4 percent of the industry in terms of numbers.

At the same time, public confidence in banks and bankers remains at historic lows.

According to a Rasmussen poll in mid-May, 47 percent of Americans lack confidence in the banking system, 15 percent say they have “no confidence at all” and one-third are concerned that they will their lose money in dealing with banks.

This latest scandal, on the heels of dozens of other revelations of unsavory and illegal behavior in the financial industry, could be the final straw pushing lawmakers to act aggressively.