“A critical part of the safety net is being both attacked and eroded in no small measure because there are no federal minimum standards for workers’ compensation”

— DOL Secretary Tom Perez

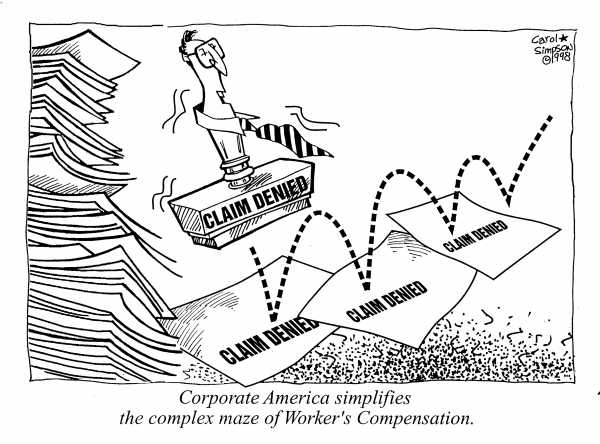

A recent U.S. Department of Labor report lays out in gory detail the problems with workers’ compensation programs in the U.S., noting that those hurt on the job are at “great risk of falling into poverty” because state workers’ compensation systems are failing to provide them with adequate benefits. Unfortunately, the DOL has no oversight of workers’ compensation programs and has not monitored state compliance since 2004 because of cutbacks.

According to the report, more than 30 states have changed their workers’ compensation laws since 2003, favoring employers far more than workers. In most instances, states have decreased benefits to injured workers, created hurdles to medical care, raised the burden of proof to qualify for help and shifted costs to public programs, such as Social Security Disability Insurance, Medicare and Medicaid.

Employers are reaping the rewards—the cost of insurance has decreased dramatically and insurance companies are paying their overages back to corporations in the form of dividends. Since 1988, the average cost to employer has declined from $3.42 for every $100 paid in wages to $1.85 per $100.

“With this report, we’re sounding an alarm bell,” Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez said in an interview with ProPublica, which had published a series of articles with NPR on the issue over the past year and a half (https://www.propublica.org/series/workers-compensation).

The Grand Bargain

Workers’ compensation was created more than 100 years ago. It was a response to challenging and horrific workplace injuries which left workers devastated and employers vulnerable to lawsuits. Labor and business compromised: workers injured on the job gave up the right to sue their employers for personal injury damages in return for less generous but more certain benefits, guaranteed pay and medical care. The compromise became known as The Grand Bargain.

In 1972, The National Commission on State Workmen’s Compensation Laws in its final report to Congress noted that “in general, workmen’s compensation programs provide cash benefits which are inadequate.”

Now, with the rollbacks of the laws’ protections, the programs are not only inadequate, they are a burden on injured workers and on taxpayers. In fact, in some instances, employers have set up a system that require workplace injuries be reported before the end of a shift, which leads to a denial of a claim of injury that only becomes apparent after leaving work or even a few days later.

“A critical part of the safety net is being both attacked and eroded in no small measure because there are no federal minimum standards for workers’ compensation,” said Perez.

In 1972, the National Commission agreed on five basic objectives for workers’ compensation programs: broad coverage of employees and work-related injuries and diseases; substantial protection against interruption of income; provision of sufficient medical care and rehabilitation services; encouragement of safety; and an effective system for delivery of the benefits and services.

No Federal Oversight Leads to State Cuts

Compliance with the report’s recommendations increased substantially over the next decade, despite no federal law compelling compliance. By the mid 1980s, though, states realized that federal intervention to enforce the Report’s recommendations was not forthcoming, and the rollbacks began.

No one was paying attention except the employers reaping the rewards and the legislatures responding to lobbyists who pushed for changes.

During the recession, states used the rolled back laws to attract businesses to their states.

Twenty-two states now set arbitrary time limits on injured workers’ temporary wage benefits. Ten states allow “independent medical reviews” of workers’ compensation claims to assess the recommendations of the injured workers’ doctors. Ten states have also increased the use of pre-existing conditions to limit or deny care after workplace injuries. There are now 37 states that restrict a workers’ ability to choose their doctor. In 18 states, employers can select the physician who treats their injured workers at least initially, according to the Workers Compensation Research Institute. In another 19 states, the injured worker is required to choose from a list of doctors — sometimes as few as four — approved by their state, insurer or employer.

“Again and again, American workers are being robbed of their rights, health protections and fair compensation,” said Rich Kline, president of the Union Label Department. “This is just another example of how the anti-government, anti-regulation agenda pushed by big business is fragmenting our laws and destroying working families in the process. No one should be pushed into poverty because they are injured on the job.”

“If you work in a full-time job, you ought to be able to put food on the table,” said Perez. “If you get hurt on that job, you still should be able to put food on the table, and these laws are really undermining that basic bargain.”

“I hope that Congress will step up,” he added. “We have to fix this system.” ■