Corporations are people, my friend,” said candidate Mitt Romney. Just try to find a jail cell big enough to hold a corporation. “Too big to fail” has allowed the United States’ biggest banks to act without restraint. Now this idea has grown to “too big to indict.”

Corporations are people, my friend,” said candidate Mitt Romney. Just try to find a jail cell big enough to hold a corporation. “Too big to fail” has allowed the United States’ biggest banks to act without restraint. Now this idea has grown to “too big to indict.”

Alan Greenspan, former Fed chair, has said, “If they’re too big to fail, they’re too big.”

What can America do to restrain these big banks? The Justice Dept. has levied fines against banks like HSBC—which was just found to have been laundering millions for Mexican and Columbian drug cartels—but the settlements are equivalent to just weeks of profit for the banks.

Other banks have also paid fines for violating U.S. banking rules: Credit Suisse, $536 million; Barclays, $298 million; Lloyd’s, $350 million; ING, $619 million; and the Royal Bank of Scotland, $500 million.

Not one executive, not one employee of these institutions, was criminally convicted. According to the Justice Dept., criminal convictions at HSBC would have led the bank to collapse and thus cause the fragile financial system to collapse as well.

According to David Cardona, a former deputy assistant director at the FBI, securing a criminal prosecution is too difficult. Civil penalties carry a lower burden of proof. Many legal experts have said the U.S. government faces an uphill battle in prosecuting financial-industry executives. Criminal intent is especially hard to prove in complex financial cases, because prosecutors must convince jurors, beyond a reasonable doubt, that a fraud was intentional.

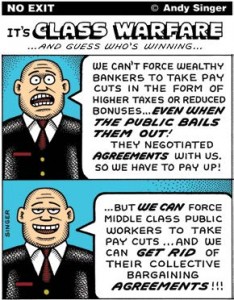

“You can do real time in jail in America for all kinds of ridiculous offenses,” said Matt Taibbi, financial reporter for Rolling Stone. “Here we have a bank [HSBC] that laundered $800 million of drug money, and they can’t find a way to put anybody in jail for that. That sends an incredible message, not just to the financial sector but to everybody. It’s an obvious, clear double standard, where one set of people gets to break the rules as much as they want and another set of people can’t break any rules at all without going to jail.”

If crime pays, as it clearly has in these money laundering schemes, the crime continues. The drug trade and terrorism continue to thrive because the criminal organizations have ways to spend their profits without repercussions.

There is generally no tax revenue generated by laundered money, so the rest of the public has to make up the difference in lost taxes. In the Libor scandal, the participating banks probably made loads of money while municipalities and other organizations saw their debt ratings decline. It’s difficult to pin down, still, how widespread the damage was from the manipulation. What’s not difficult is figuring out that no one in the U.S. has suffered a criminal charge from the manipulation.

The Dodd-Frank regulations were put in place in 2010 to regulate the financial industry and include a process for liquidating or breaking up failed big

banks known as resolution authority (without resorting to bailouts). It’s supposed to subject the large institutions to more stringent oversight and give the government the power to liquidate a bank that has overstepped its bounds.

Former Rep. Barney Frank, who sponsored the Dodd-Frank law, called resolution authority a “death panel” for banks, but still, the 10 largest banks control 54 percent of the deposits in the U.S. No one is using the authority of Dodd-Frank and the largest banks are still acting with impunity.

On July 25 2012, former Citigroup Chairman and CEO Sandy Weill, considered one of the driving forces behind the considerable financial deregulation

and “mega-mergers” of the 1990s, surprised financial analysts in Europe and North American by “calling for splitting up the commercial banks from the

investment banks. In effect, he says: bring back the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 which led to half a century, free of financial crises.” Using the authority of the Dodd-Frank or returning the regulations imposed by Glass-Steagall clearly needs to be a focus of U.S. regulators if they want to rein in any future misdeeds.