When Bank of America and Wells Fargo tried to foist off expensive new debit card fees to customers earlier this year, the move touched off a consumer revolt that yielded 650,000 new accounts and infused some $4.5 billion in new business for credit unions in the space of a month. It also added momentum to the public banking movement, a grass roots effort encouraging states to consider laws that encourage publicly-owned banks that could revive community banks and open up the spigot for affordable and reliable small business and consumer credit.

When Bank of America and Wells Fargo tried to foist off expensive new debit card fees to customers earlier this year, the move touched off a consumer revolt that yielded 650,000 new accounts and infused some $4.5 billion in new business for credit unions in the space of a month. It also added momentum to the public banking movement, a grass roots effort encouraging states to consider laws that encourage publicly-owned banks that could revive community banks and open up the spigot for affordable and reliable small business and consumer credit.

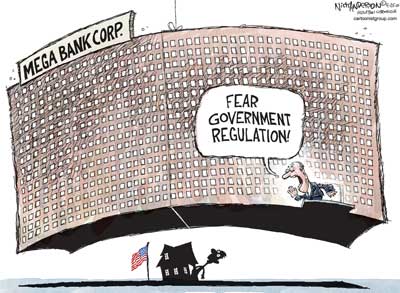

Earlier this year, the big banks had wanted to recoup expected “losses” they would experience under new consumer protection regulations contained in the Dodd Frank law that limited what they could charge merchants for using credit and debit cards. They also tried to create a consumer push back against the legislation. Their plan didn’t work. According to consumer reports, bank customers are already saddled with an average of $327 a year in “hidden fees” just for checking

accounts from the big banks and the new fees felt like salt in a wound.

Combined with the bad publicity banks have earned with high-handed foreclosure practices and revelations about slap dash record keeping, America’s big banks appear to be veritable billboards for arrogance. The unintended consequence of the planned fees was a stampede of customers who moved their accounts to credit unions.

The Federal Reserve says 30 huge companies dominate the banking and finance landscape and have for the past decade. These are the same companies that preyed on hapless homeowners; marketed high risk loans to individuals and small businesses that could not afford them; bet on the failure of their own customers with credit default swaps; rigged bids in big credit deals; and enjoyed windfall profits. (Bank revenues increased by over 48% this year, and profits through the 3rd Quarter of 2011 were up by more than $11 billion from the previous year.) These same bankers just couldn’t understand the lack of “loyalty” their customer base demonstrated. Oh well, who needs customers when you’ve got politicians eager and willing to shovel trillions of dollars worth of welfare to bail you out when deals go south?

A decade ago, banks had to choose between either providing traditional banking services—checking and savings accounts, residential and commercial loans—or selling insurance and investment and brokerage services. Passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley “Financial Modernization” Act enabled the big banks to become financial supermarkets. In 1990, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, there were 15,162 financial institutions with assets totaling $4.6 trillion; in 2010, there were 7,657 with assets totaling $13.3 trillion. Less than half as many banks holding three times as many assets.

The Public Bank Movement

It’s pretty clear on Main Street that the movement to ginormous banks has been a key element in America’s financial morass. The disappearance of community banks with their connection to local businesses and ordinary depositors is deeply felt. Putting that egg back in its shell may not be possible, but the movement toward publicly-owned banks, with a chartered obligation to citizens of a specific jurisdiction has an appeal. In Oregon, activists have linked public banking or “partnership” banking to the “think local” concept. In legislative hearings around the state, supporters have pressed the issue with the

slogan: “buy local, eat local, bank local.”

The U.S. banking and finance industry reported spending $47 million this year for lobbying and contributed more than $123 million to help re-elect members of Congress last year—led by Goldman Sachs ($1.158 million); Bank of America ($1.067 million) and the American Bankers Association ($981,950).

Goldman Sachs enjoys a special place in the hearts of at least 19 incumbent members of Congress who hold Goldman Sachs stock. The portfolios average $812,900. According to the Open Secrets Blog, both House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) and his second in command, Erik Cantor (R-VA), are among the 19.

The Public Banking Institute (www.publicbankinginstitute.org) is the focal point of efforts to get states to investigate the public option. So far, PBI has

established a presence in 32 states and has set up volunteers to coordinate state information and lobbying efforts in 24 of those states. PBI is recruiting volunteer coordinators in the rest of the states through its website.

Setting Up Public Banks

PBI reports that 14 states are actively considering legislation related to public banking; more are expected to pick up on the issue in the 2012 legislative sessions. PBI’s website points out that publiclyowned and managed banks offer substantial benefits, not limited to the obvious revival

of community-based banks with their connections to local businesses, entrepreneurs and homeowners. For example, they say, it’s no coincidence that North Dakota—currently the only state in the nation with its own bank—has weathered the recession with consistent economic growth, an unemployment rate of under 4% and without a state budget deficit.

For states groping for alternatives to persistent budget cuts and reduced services, state-owned banks offer the advantage of keeping assets—pension funds, tax revenues, rainy day funds, capital improvement funds—within the state’s borders and out of the hands of the monster global banks (on Main Street and away from Wall Street).

After more than three years of austerity budgeting, still 48 of the 50 states continue to face gaping deficits (expected to reach $46 billion in the coming year). Double-digit unemployment has choked off tax revenues to a trickle in most states. In the frantic search for a magic formula to replenish state coffers devastated by the longest and deepest economic disaster since the Great Depression, states under the control of conservative lawmakers and governors have attacked collective bargaining and initiated deep and permanent cuts to their budgets for education and public services—firing public safety workers and teachers, eliminating libraries, cutting transportation services, and reducing infrastructure investment to a bare minimum. Some states have turned to expanding legalized gambling. By now its clear: those ideas are proving inadequate for closing budget gaps and—in the long run—unworkable.

Commercial Bankers Opposed

The American Bankers Association (ABA) opposes state banks, calling the concept a “socialist idea” and claiming that startup costs would run into the billions. Countering the ABA, PBI points out that most states already have more than sufficient cash assets that are now being managed by big commercial financial institutions, cash that would easily be convertible into a publicly managed bank. Using the generally accepted leverage ratio of $10 to $1, it would take just a fraction of those assets to set up a state or publicly run bank. Moving that money would not undermine the earning power of these funds. It could, however, help make credit available to small, local businesses, something the big commercial banks currently refuse to do.