It’s not quite a trend when seven major U.S. corporations get together to search for small businesses to act as “local sources” for their supply chain, but it is an indication that offshoring is losing some of its luster.

AT&T, Caterpiller, Bank of America, Citigroup, Pfizer, UPS and IBM recently announced a joint effort to identify small businesses in the U.S. to sign up on a

contractors network. The initiative is open to any of the 9 million small businesses in the U.S. However, only 200 had submitted the formal application as of January.

Business bloggers and publications are spotting other indications that boardrooms are beginning to realize that sending work off to China, India and other

far off points did not bring about the economic boom they had expected. When transportation costs, carbon footprints and loss of control are factored into cost calculations, manufacturing and even service sourcing in far off places looks more expensive than domestic costs.

As a report by the consulting firm Accenture notes: “Companies are beginning to realize that having offshored much of their manufacturing and supply operations away from their demand locations, they hurt their ability to meet their customers’ expectations across a wide spectrum of areas, such as

being able to rapidly meet increasing customer desires for unique products, continuing to maintain rapid delivery/ response times, as well as maintaining

low inventories and competitive total costs,” and that “managing supply operations that are separated far from where demand occurs has weakened their overall operational planning, forecasting and general flexibility, while in some cases driving up costs with the need for complex network management.

In some cases, this situation has limited the companies’ competitive advantage.”

There is another factor to consider: while the purchasing power of the U.S. middle class is shrinking, the middle class in the developing world is expanding.

China, for instance, is the largest market for automobiles today.

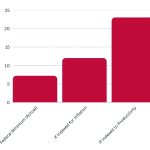

According to the World Bank, developing nations accounted for 56% of the world’s middle class in 2000; By 2030, 93% of middle class will be in the

developing world, with China and India accounting for most of that expansion.

Therefore, multi national corporations are going to concentrate their growth plans in those areas and unless the U.S. middle class begins to grow again, there won’t be much point in expanding productive capacity here.