Amazon.com announced at the end of September that they were going to create an “Uber” version of their delivery service. You could work for Amazon, set your own hours, and deliver packages for them using your own vehicles.

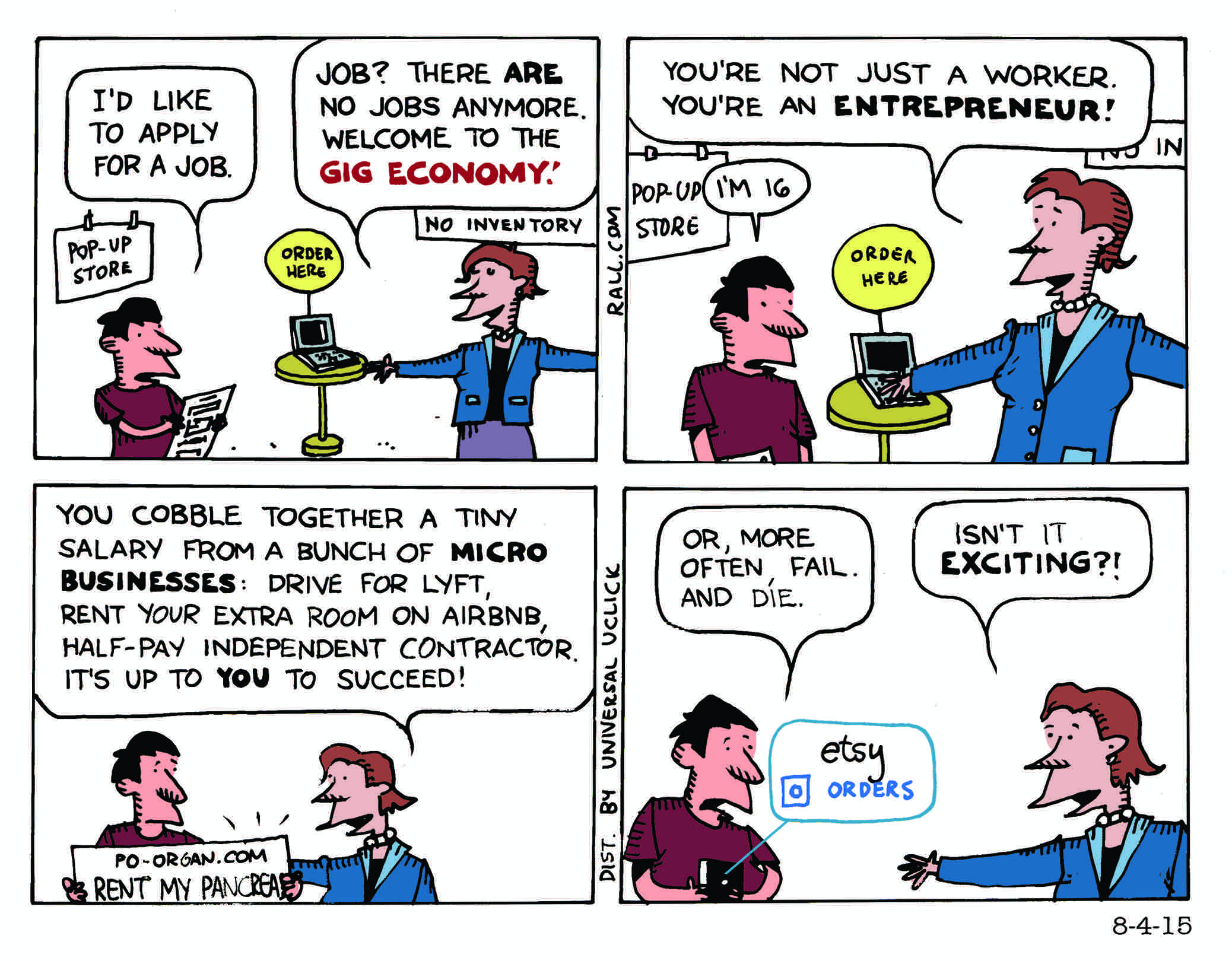

This is quickly becoming the new normal. Uber, AirBnB, Etsy. The U.S. workforce is rapidly becoming a workforce of freelancers or contractors. No one is employing them, supposedly. Ostensibly, workers are able to come and go as they please, set their own hours, and bill the company for their work. While there are no definitive statistics around the number of workers involved in the on-demand economy, consulting firm MBO Partners estimated 17.9 million people worked in 2014 as independents for 15 hours or more a week.

But in this “gig” situation, what is really happening? Companies are the real winners. Digital hiring halls may give workers freedom to work whenever they want, but these workers are denied the type of worker protections provided to those employed by corporations or other organizations. Companies evade paying health care, unemployment compensation, auto insurance (for those in driving professions), and workers compensation. Companies also evade overtime laws. Workers must pay their own employment taxes and their social security.

In advertising for drivers, Uber, for example, claims that drivers can build their own businesses, making up to $90,000 per year in some areas of the country (for example, New York and parts of California). But that claim doesn’t account for the 15.3 percent the new “business owner” has to pay out-of-pocket for his Social Security and Medicare taxes, in addition to insurance, car maintenance and repair, as well as gas and tolls.

Amazon Mechanical Turk is a “crowdsource marketplace” that relies on freelancers to scan image sites and label the photographs and images appropriately, de-duplicate data, such as phone directories or product catalogs, or double-check restaurant listings, write product descriptions or transcribe podcasts. It is estimated to employ around 500,000 workers. One of the researchers for the National Employment Law Project found that “90 percent of tasks posted on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk paid less than 10 cents.” Further, the researcher determined that “a task worth $1.00 with an average completion time of 12.5 minutes resulted in an effective hourly wage of $4.80.”

How will Amazon.com delivery drivers, who won’t get tips like Uber drivers, perform in this employee-as-an-independent-contractor reality? If the employee can’t work for a few weeks because of a disabling illness or other issue, he misses out on those hours. If a delivery driver gets into a car accident while carrying Amazon packages, does the driver’s insurance have to cover the cost of the accident? If the business decides to sever its relationship with the driver, there are no unemployment protections – the company is not the employer, just the “facilitator,” according to their business model.

Many are touting these jobs as the future of the workforce. There are claims that gig jobs create a better work-life balance, allowing for those in these jobs to choose their work hours can mean that they can take an hour to pick up their children from school or coach soccer. For Etsy and Ebay-type sellers, who are likely using the Internet to sell hand-crafted items as a side job or hobby, the work-life balance is probably already in place, but for an Uber or Amazon.com worker? If the drivers can’t meet quotas or make their ratings, it’s not likely the company will keep using them. Turning down work will likely mean a black mark on their record, and less likelihood for a call next time. In fact, according to court documents, Uber eliminates drivers who have low “dispatch acceptance rates” and will deactivate driver accounts when the market is saturated or business is slow.

And what about long-term stability? There are no guarantees in on-demand work. It’s harder to plan life longer term when it’s unclear how much money you’re going to be making next year. There are no paid vacations or paid sick leave and retirement planning is entirely up to the worker.

The National Employment Law Project issued a report in September that called for labor standards to protect on-demand workers as well as those employed in traditional workplaces.

RIGHTS ON THE JOB: Like other workers, on-demand workers should enjoy the protection of baseline labor standards, including the right to the minimum wage for all hours worked and the right to a voice on the job. The label assigned to a worker by an on-demand company should not determine or defeat their ability to have decent jobs. Workers in app-based jobs also need new protections to guard against the misuse of company-held data.

SOCIAL INSURANCE PROTECTIONS: All workers need and deserve the protections afforded by basic social insurance programs. Businesses in the on-demand economy should not get a free pass on making contributions to existing social insurance programs, such as Social Security, Medicare, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance, on their workers’ behalf.

And the social insurance programs now being developed, such as earned leave and supplemental retirement savings, should extend to on-demand workers.

BROAD AND EQUITABLE ACCESS TO TECHNOLOGY: If the future of work is that we access it via the Internet, all workers should have meaningful access to the necessary technologies to secure it.

The isolation of workers in this digital on-demand age gives companies an unfair advantage. Taking action, such as unionizing, or even demanding basic benefits, can be impossible for employees who’ve never even met their bosses in person, let alone a co-worker. According to NELP:

New technologies should not be allowed to displace existing protections for the many on demand workers who are, in fact and in law, employees. We must ensure that these workers’ rights are recognized and enforced. As new technologies develop, we must also develop new models of delivering core labor rights, including the right to take collective action aimed at expanding those rights and adapting them to specific industries.

Unions are exploring ways to reduce gig worker isolation so that they can band together to demand their rights. Creating networking events or social events or even collaboration events geared towards these workers will help build camaraderie among these workers and show them a way to get a voice.

MISCLASSIFICATION

OF EMPLOYEES

California’s Labor Commission ruled in June that an Uber driver was actually an employee of Uber. The decision said that because Uber controls the tools the driver uses, monitors their performance and can terminate them if they fail to achieve the company’s predetermined rating, drivers were employees. Eight states have issued rulings that classify Uber drivers as independent contractors: Georgia, Pennsylvania, Colorado, Indiana, Texas, New York, Illinois, and California, which made such a ruling in 2012 that applied to only a specific case; but Florida, Utah and now California have found otherwise. Uber has had at least 100 lawsuits filed against it.

Lyft, another on-demand ride service, faces at least one misclassification lawsuit and has faced several others previously. A class action suit filed in July against the home services company Handy claims that it has violated the Fair Labor Standards Act by failing to pay minimum wage and misclassifying its workforce as contractors. A similar company, Homejoy, shut down after facing lawsuits on misclassifying its workforce.

The on-demand meal company Sprig changed its so-called contractors to full employees in August after facing significant pressure. In an interview, Sprig founder Gagan Biyan said, “One of the reasons we’re moving to employees is to offer more training and development to better communicate our mission. We’re starting to take our inspiration from fine dining restaurants, with our servers [delivery people] being able to talk to you at your door about your meal.”

A grocery delivery company Instacart also changed its employment model for its shoppers in several of its locations, claiming that they needed to provide more supervision and training to its workforce because “grocery shopping can be complicated,” according to CEO Apoorva Mehta. It has not moved its drivers into employee status, however.

Other companies providing on- demand services have classified their workforce as employees and found success. A personal assistant company called Alfred, an office cleaning service called MyClean, and a mailing company called Shyp, issue their workforce W2s. Shyp made the change because, it says, it would gain efficiency, be able to train its workforce, review their performance and direct them to accept jobs. Munchery, another company that has changed its workforce to employees, has said that “it became much easier to expect them [its workers] to show up on holidays or Sundays.”

Handy had a provision in its terms of service that if it were found liable for back taxes on its workforce, it would pass that liability onto its customers. The provision told customers that if Handy were found liable the customers would have to “imme-diately reimburse and pay to Handy.com an equivalent amount, including any interest or penalties.”

When the Wall Street Journal investigated the provision, Handy removed it. However, it has said that if it loses its pending lawsuits, it would have to raise its rates and drop its hourly pay to contractors. ?