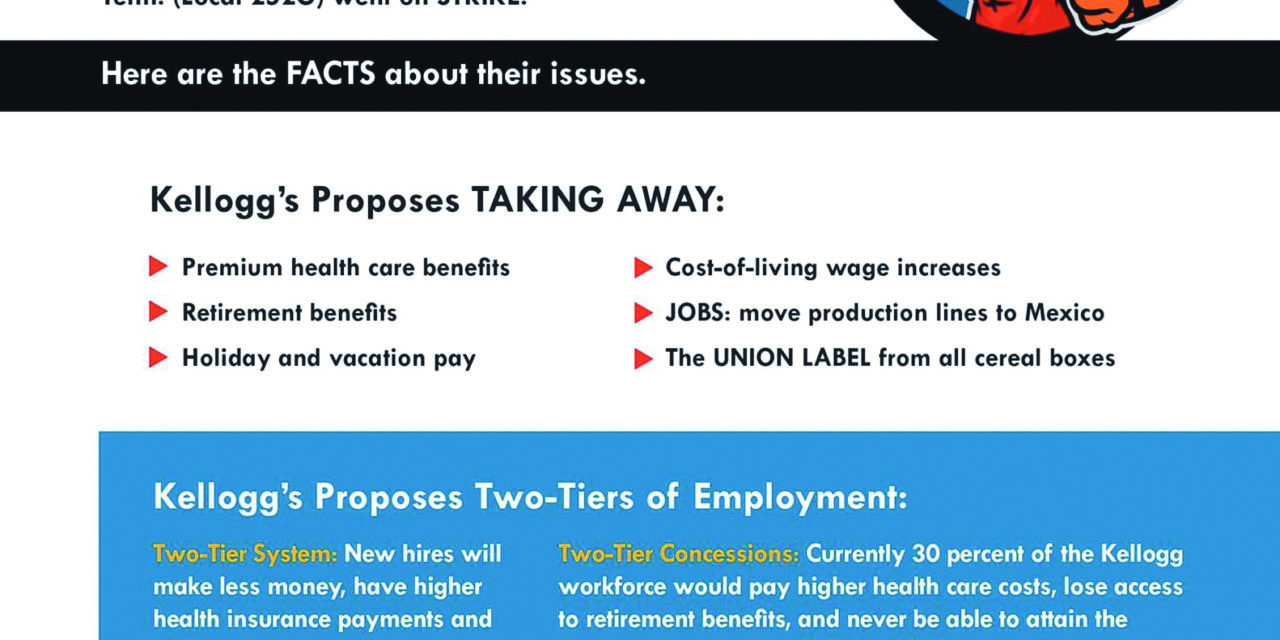

On October 5, 1,400 BCTGM members at Kellogg’s cereal plants in Battle Creek, Mich. (Local 3G), Omaha, Neb. (Local 50G), Lancaster, Pa. (Local 374G) and Memphis, Tenn. (Local 252G) went on strike against their employer. The strike stemmed from Kellogg’s proposals to modify or take away health benefits, retirement benefits, and vacation pay and to remove the Union Label from cereal boxes.

The workers also claim that the company’s proposal to remove the union label from boxes is a precursor to moving more of their work into Mexico, muddying the consumer’s ability to determine where their cereal was made.

Another issue prompting the strike was the proposal to expand their current two- tiered employment system, with new hires making less money, paying more out-of-pocket for health insurance and having no access to pension benefits.

Their last contract created a class of “transitional” employees who are paid lower and receive lesser benefits. The contract stipulated that the transitional employees must have a path to become so-called “legacy” employees and that no more than 30 percent of the existing workforce can be classified as transitional. As older employees quit or retire, the transitional employees move into the legacy status. Kellogg’s is proposing an elimination of the 30 percent cap, making it impossible for the newer workers to ever reach the higher paid status.

Although pay rates vary by position, workers said there is currently a roughly $12-per-hour difference between legacy employees and transitional employees in many roles. Transitional employees pay health care costs that their legacy counterparts don’t and are on a lesser retirement plan.

Kellogg’s claims that employees can make around $120,000 a year, but the striking workers counter that claim by pointing out that to make that much, they had to work overtime including 12- or 16-hour days, often seven days a week.

In an article in the Huffington Post, Kellogg’s worker and BCTGM Local 3G President Trevor Bidelman, who is a fourth-generation employee at the plant, told the news outlet, “When you look at the Battle Creek area, getting into Kellogg’s was a career,” he said. “Now they want to turn it into a job. What they don’t understand is you’re only in a job until you find a better one and grab it.”

“This fight is about the people coming up behind us. We’ve got to say enough is enough.”

On the overtime issue, Bidelman said his longest personal stretch of consecutive workdays without a break was 116.

Many unionized companies would rather pay an overtime penalty with their existing workforce than hire more employees entitled to benefits under the union contract.

Two-tier systems are used by employers to help drive a wedge between the workforce. When the employees agreed to the two-tiered contract six years earlier, they did so because the company was threatening to move jobs out of the country.

By removing the cap on transitional employees, Kellogg’s would be able to exacerbate the discord and further erode union power. ■